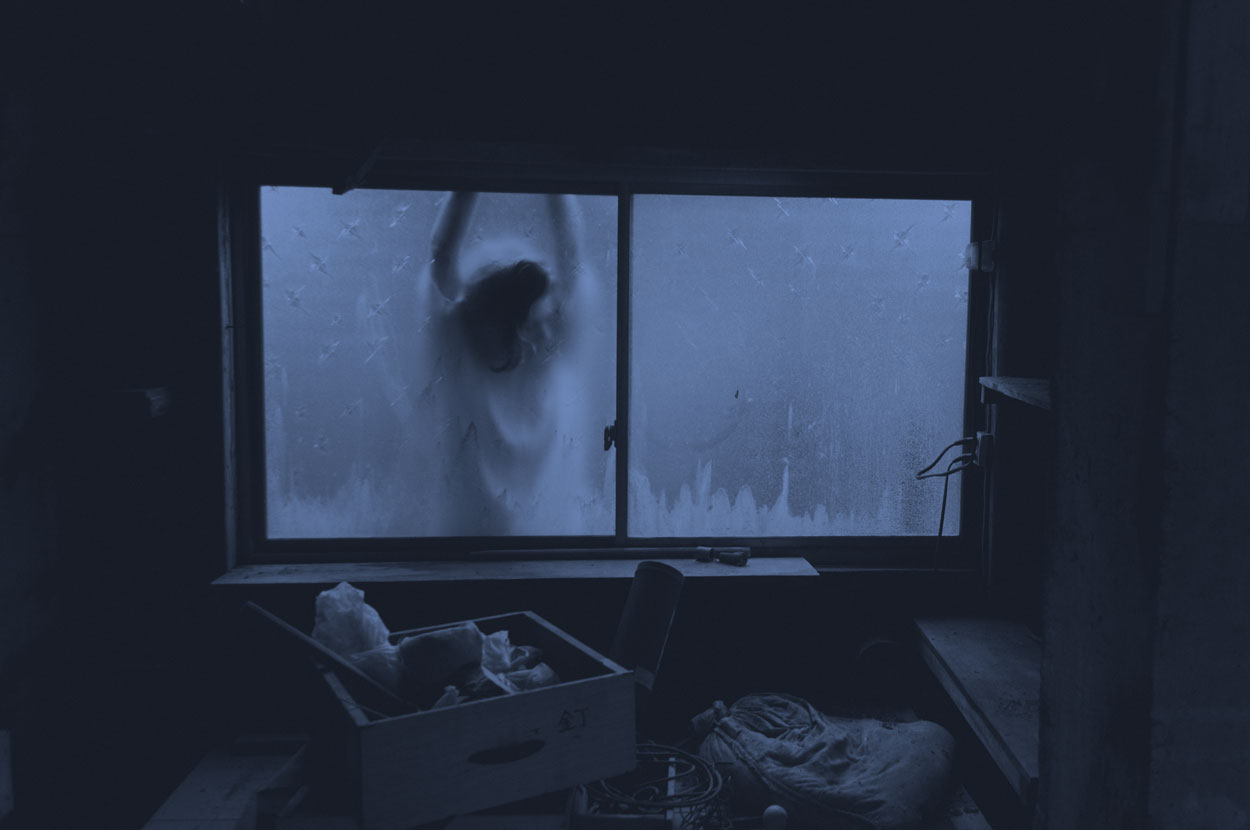

An atmospheric look into a haunted basement and the secrets in a small town.

2,500 words. Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash. Originally posted on Theme of Absence in October 2017 which also posted an interview with me.

People don’t really keep map collages. You see them on TV because it’s a clever way to visualize a thought process. To let the viewers glimpse the obsessive madness. But it’s TV fiction, like doors that are always unlocked, and guns with more than six rounds.

“I think it’s neat.” Tuet spoke as though responding to my thoughts; or maybe my scowl of disbelief. She pushed at the old-fashioned mounted cork-board, the kind in a wooden frame, the legs like upside-down Ys; it squeaked across a few inches of cement basement floor. “The latch is rusted.” She kicked at it.

I traced a finger over the flaking cork, with its brass pushpins, and taut strings; the yellowed, curling newsprint. “Who does something like this?”

Tuet grunted, still trying to engage the latch over the wheels. “Someone who had to plan something, I guess.” She brushed her hands off on her jeans. “Everything down here is so filthy. Well, I just can’t get this thing to budge. What do you say we tackle these boxes instead?”

I shrugged. Made no difference to me what order we worked in. Everything had to go.

It’s a pleasant small town, even these days. Green, rambling yards, quiet streets, old trees, folks on porches. I would never have chosen it alone, the downtown is my milieu, but Tuet had happy memories growing up here and for the price of the down-payment in the city we had a whole house to ourselves. Who could argue with that?

We both worked from home, so our first real reno effort went into upgrading the wiring, putting in high-speed, and converting the two spare bedrooms into offices, one each. A far larger job than either of us prepared for, and we left the unfinished basement alone as priorities shuffled. Boxes of old dishes and stacks of Nat Geos could keep a few months more. They had already been there for years.

“I wonder if our designs will be this dated,” Tuet said one night, her mouth full of the crispy fish casserole her Aunt Mei had brought over. She chewed absentmindedly while leaning on the Formica-covered kitchen island. “This must’ve been fashionable when they first moved in.”

I shook my head, and speared a veggie with my fork. “This was never attractive.” I indicated with my be-bean’d utensil the scope of the hideous decor. “Purple tiles? Brown walls? Green-marbled Formica? They must’ve been blind as well as crazy.”

She wrinkled her nose, amused, but unwilling to admit it. “Don’t be mean.”

“I’m not. Being factual.” I pulled the Pyrex dish over, picking out a cube of fried fish. “It’s a fact.”

“That their idea of good interior design was wrong? That makes them crazy?”

I shook my head. “No. It’s that map board downstairs that makes ‘em crazy. The decor just gives them poor taste.”

She stopped, fork halfway to her mouth, head tilted. “The what?”

I smirk. “You know. That cork-board.” She chewed, thoughtful, unconcerned. “You know! That stupid hunk of crap in the basement!”

Her turn to smile indulgently. “There’s a lot of crap in that stupid basement. They must have just been on the edge of hoarders, or something. Maybe there’s something valuable…” She continues, a litany of potential antiques, treasures hidden in crumbled newspaper, but I stopped listening. It seemed odd that she’d forgotten about the cork-board. Yes, we had been busy but I hadn’t forgotten; it lurked in my memory, ever on the edge of recollection.

While Tuet washed the dishes, I stood at the top of the basement stairs. The staircase–wooden, creaky, and coated with cobwebs as all basement staircases of certain vintage must be–was lit by a bare bulb, its switch on a graying string near my head.

As I pulled, I reflected on how silly I was being.

The set of switches at the base of the stairs flicked on bigger lights and dispelled that gloaming with warm, benevolent incandescence. And yet. Corners remained unlit. Curving shadows encroached.

Berating myself helped dispel my heebie-jeebies. Somewhat. But each newly-noticed spiderweb, each breath of stale, earthen air threatened my logical facade.

Get. A hold. Of yourself.

The cork-board sat where we had left it, a foot away from the wall on one side where Tuet had fought with the latched wheel. My eyes roamed over the patchwork of strings, handwritten notes, old photos, newspaper clippings. The map was of our tiny corner of the world, mostly rural but close enough to civilization by highway.

The clippings, I discovered, were all of local landmarks and all equally gruesome. A murder from 35 years ago; two generations of domestic feuds; accidents; stillbirths; every unfortunate story a small town might find fit-to-print. Accompanying the newsprint were the handwritten notes of incidents too private or too small for even the county newspaper. Someone had been very busy, for a very long time, keeping watch on their community.

“Did you know that Weber’s grandfather lost a hand, here in the hardware store?” I whispered, as Tuet examined tubs of Polyfilla.

“What?”

“When this place also handled lumber, before the Home Depot on the edge of town. Newly installed bandsaw.”

“What?” Sudden focus. Now I had her attention.

I nonchalantly picked up a tin of varnish. “Yep. Police suspected that old man Weber and his brother Gerry had had an argument that had turned sour, but they never proved foul play. Put down as an accident.” I gestured with my chin towards the front counter where there hung a framed portrait of Our Founders, Harold and Jerry, Part of Our Community.

“I never heard about that.” Tuet’s mouth swung open. “And I grew up here. Who’d you hear that from?”

I smiled. “He bled out in the back room.”

Astonishment turned into disgust. “That’s just gross. Don’t be so creepy.” Tuet grabbed a tub of ‘filla and stalked off.

We left Weber Bros. Hardware, as the sun emerged from behind a cloud, turning a dreary March day more cheerful. As we tossed bags into the car, my mind on the weather, Tuet startled me. “What? Sorry, I was thinking about…”

“I said,” Tuet interrupted, in a quiet, exasperated tone, “How do you know about that? Back in the store?”

“The Weber thing?”

Nod.

I shrugged as I started the car. “Read about it on that map-board. Collage. Map-board-collage thing.”

Tuet was quiet the whole ride home.

She proceeded down the rickety staircase one step at a time–both hands on the dusty boards that served as rails–at each riser making sure her feet were firmly planted before moving on. She said it was the staircase’s sway that bothered her. She crossed the concrete floor as easily as the carpet in the living room. I more slowly made my way, hearing the hiss of dank history with every step.

She examined the collections of clippings avidly, probably because the names of places and families were familiar to her; her childhood community, after all.

Tired of the murmuring, and unenlightening remarks like “oh, I lived down the street from them”, and “so that’s who Maggie’s aunt remarried”, I turned my own attention to wander the clippings.

“That’s odd.”

“I know, I would’ve thought that the Brubakers would’ve stayed–”

“No, I mean this.” I flicked the corner of a 3×5 index card, faded lines covered in scrawl with more detail about Harold Weber’s ill-starred bandsaw, involving Gerry’s indiscretions with a pretty young salesgirl. “This wasn’t here before.”

Tuet peered at it for a moment then moved on. “You probably didn’t notice it because it was under something else. There’s a lot here.”

I deciphered some of the ballpoint scribbles. “I think I would’ve remembered details like this.” I tapped the card. “No one would make up stories this sordid…” Then: “Are you doing this?”

“What?” Genuinely startled. Perplexed, even. “What do you mean?”

“These cards. Are you rearranging them on me?”

“Why would I do that?”

“As a prank! To freak me out. You know how creepy I think this house is.”

She laughed at me, repeating: “Why would I do that?”

“I don’t know! A silly joke…” I trailed off, running my hands through my hair. “That card. That–it wasn’t here before.”

“You’ve only been down here couple of times right?” She flicked through some curled paper. “With all the work we’ve been doing, the details on here must’ve just slipped your mind.”

It was so reasonable.

Gray March and damp, rainy April blossomed into lush, green May. Every part of the house got aired, the sash windows propped up with bits of wood or old paint stirrers. We finished the reno and settling into a good working routine. The drafts in the house no longer recalled neglect, but lilacs. Then the news came to us: Tuet’s grandfather had passed away back in Hu Long. She would have to go. Most of her family would be there.

“It’s going to be weird,” she said for the hundredth time, in the passenger seat, as we drove along the empty highway bound for the airport.

I mumbled assent; even the extra-large coffee had limits–3 am is hard. Tuet hadn’t slept. She stared out the window at the black country side. Wide-eyed from both a dread of funerals and excitement of going back to the country she’d only visited once as a teenager had furnished her with last-minute energy.

“When I get back, it’ll be good weather to tackle the basement,” she said as I zoned in and out of her nervous chatter, focused on driving. “Garage sale season.”

I imagined neighbour’s faces as they read their family secrets on yellowed index cards, tacked with rusty pushpins, coated in scotch tape residue and falling apart from decay. Some garage sale.

After the long drive home, all I could do was crawl upstairs to bed and collapse, my eyes sore; my lower back worse. I should’ve forced myself to stay awake until a more reasonable bedtime, but I was weak.

It was just after midnight when I awoke, refreshed. I read for a bit in bed, then got up to make something to eat, planning to take some sleep medication to knock me out and put me back on my regular schedule.

As I made my sandwich in the darkened kitchen, I noticed the basement door. It wasn’t ajar, or lit from underneath, or anything cinematic like that. It was simply more real, more vibrant, than anything else. As though it was a photograph with a shallow depth of field: everything around me but the door was a little blurrier, grayer. Weaker.

My hand touched the doorknob, although I don’t remember forming the desire to go downstairs. But I must have.

The bare, overhead bulb hurt my eyes, yet barely punctured the heaviness of the black space at the base of the stairs. I wanted to go back to my sandwich, to my sleeping pill, to my bed; but every step took me further down.

My fingers found the light switch. My eyes adjusted and the light blazed warm and inviting, even while the concrete under my bare feet stayed shockingly cold.

There stood the board, still not flush with the wall. Still the same as ever–

A new string.

A new string, long and faded red, from the near the centre of town–our house–out across the counties. To the airport.

I ran, leaping the stairs two at a time, grabbed my bag and jacket, and fled to the neighbours.

“I don’t understand. There wasn’t a break-in?” Tuet hauled her bags from the trunk. “Then why did Auntie Mei say that she heard there was?”

“The Steinbeckers must have told her when they phoned about her cat,” I explained. “Look, they thought I’d heard a burglar; I didn’t correct them. I wrote all this–”

“I told you, I had no signal most of the trip.” Tuet still wore the same confused expression from the last leg of the car journey, after she’d finished gushing her anecdotes and family stories, and listened as I told her about that night.

I had come home the next morning and barricaded the basement door, as though boxes and an armchair would defend me. I’d even done the same with the kitchen door, and avoided the entire main floor for as much as possible for the following two weeks, living off sandwiches from the corner store five blocks away.

Tuet dumped her suitcases inside the front hall, then pointed at the walled-up kitchen door with her puzzlement refreshed.

“I know, I know. But there’s something down there. Something that’s been following me.”

Her dark eyebrows pulled together, transforming puzzlement into an equally fierce determination.

“Show me.”

In the daylight–feeble and severely slanted–the basement seemed harmless. Gloomy, certainly, but an earthen, nonthreatening dankness. Still, I stayed on the last step.

Tuet pushed forward, fierce or reckless, peering at the board, twanging the string that had appeared. It snapped with a puff of ancient dust.

“Now that you mention it, these clippings are all of the places we’ve been, but there are only so many places to go around here, I guess I just figured–”

I cut her off, casting my voice from across the room. “That clipping is new. Where’s it for?” I pointed, directing.

Her jaw dropped. “It’s for a section of the airport that burnt down, from suspected arson in the 70s. Twenty-two people were killed. It’s… the site of the rebuilt international arrivals terminal. That… That wasn’t there before I left.”

The two of us could barely shove it up the stairs; awkward and heavier than it looked, it seemed to catch on every gap or corner possible. Like it was struggling against us. Out in the backyard, we heaved it onto the grass. While Tuet made an impromptu fire pit, I popped round to the Steinbeckers to borrow a small axe. Mr. Steinbecker graciously offered to take care of any logs we needed resizing with his chainsaw, curiosity written across his features, but I assured him we could handle it.

The middle-of-a-May-afternoon bonfire attracted attention from either side of the property, but the neighbours declined to ask and we didn’t offer.

Cork and dried newspaper burns very quickly. Excellent kindling.

We had a quiet supper. Neither of us could make much conversation, the evening dragging on until it was late enough to justify going to bed. It was a little after midnight when I woke, wide-eyed in the darkness, smelling the smoke.

We watched the blaze, Tuet and I, swathed in blankets, from the running-board of the ambulance. The county firefighters tried to save the house, and protect the others if the fire spread.

Tuet worried about the tut-tutting we could expect from the neighbours and her family about the impromptu bonfire, but I knew–and later the fire chief would confirm–that fire hadn’t started in the yard.

It had started in the basement, the last place we’d been, at a little after midnight of the following day.

END

Leave a Reply